Building a Pebble app with C, JavaScript and Rails (Toronto Transit Time)

Earlier this year I was looking for an app that showed predictions for Toronto streetcars/buses on my Pebble smartwatch. To my surprise, I could not find a single one that worked the way I expected it to (or that worked at all, to be honest), so I decided to build my own.

Little did I know that getting fast and reliable predictions on my wrist wasn’t just a matter of writing C code on the watch - it also required code running on the phone and on a server. Totaly worth it: I use Toronto Transit Time almost daily - and I’m not the only one.

This insight of the development process was originally intended to become a presentation for the likes of PebbleTO, but given the uncertain future of Pebble (recently acquired by FitBit), I decided to just publish it here as a supplement to the application’s source code.

Inspiration

People often buy smartwatches expecting them to be as useful as their smartphones, but quite often it’s all about notifications and a couple apps that work well in situations when reaching to one’s pocket would be cumbersome or dangerous.

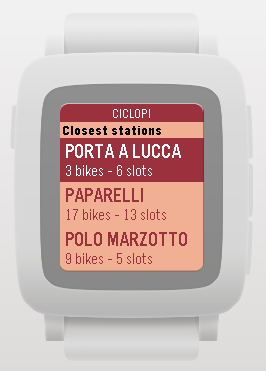

One such app is Bike Sharing by Andrea Ferrato, which quickly locates nearby bike rental stations and shows the available number of bikes and empty docks on each one. Sure, there are lots of great phone apps to get that info. But when I’m on a bike, trying to figure out where to dock, picking up the phone isn’t an option.

In the winter (when public transportation trumps bikes), a likewise situation happens: I’m wearing gloves, it is cold and I need to quickly decide to which stop to go - and whether to do it now or wait at the nearest Tim Hortons. Toronto has open APIs for retrieving this information (which can be perceived by the numerous displays in private and public locations), so I thought that (in spite of my rusty C skills) I could put that information on a watch.

Design

Before considering the look and feel of the app, or how to build it, it was important to acknowledge the main restriction: the Pebble hardware itself. The watch display is a low-res, black-and-white screen (later models improve that slightly), and the only inputs are four buttons. These features map pretty well to a list selection UI (the right-side buttons usually work as up/select/down, and the left one goes back). Bike Sharing was a prime example of that pattern, so that would be it.

Another important factor were the APIs - in such a tight environment, a design that didn’t match the information architecture would be a recipe for failure. Toronto Transit Company (TTC) publishes information about stops, routes, directions and real-time predictions by means of NextBus (and so do several other public transportation companies). Their API (documented for TTC here) makes it easy to figure out which routes serve a given bus stop, and for a given bus+route pair, a single call reveals all the upcoming predictions. It only serves XML like this (at least officially), but otherwise it has all I needed - except one thing: geolocation.

The API seems to be designed for those displays, which are focused on a single stop (for which you already know the ID), or for map-based APIs (which will likely make all of them available). On the Pebble, we only have a latitude/longitude pair. Sure, we could have it (pre-)fetch the full list of bus stops on the phone, and even figure out which ones are nearby. But that would result in increased consumption of CPU (battery), storage and data. No way, Jose.

The solution was to add a server of my own to the mix. It would fetch the information periodically, do the geolocation math and give the Pebble needs to show (except the predictions, which would be delayed by that). Not as simple as a watch app, but would avoid any UI compromises, so I went with that.

Architecture

Pebble App (C language)

A Pebble app is usually written in C, consisting of a set of stackable screens (which it names Windows). My initial idea was to have one window listing the stops, a second with the routes and a third with the details - which would mean two navigations (up/down + select) to get the information. Fortunately, MenuLayer (the selectable list component that we see in lots of apps) can group its menu items in headers, so I could display the stops on headers, and the routes on menu items themselves, making it a single navigation.

To be honest, I considered including the prediction information on that menu as well (like Bike Share does with the bike/dock counts), but that data needs to be fetched on an individual basis. As a compromise, I settled on two screens: routes (grouped by stop) and predictions.

I added a “splash screen” layer that I could overlay whenever anything was loading - from the app itself and the initial routes list to the prediciton refreshes. The streetcar illustration and the text (changing as each step is performed) distract the user from the wait - which is usually in the sub-second range anyway.

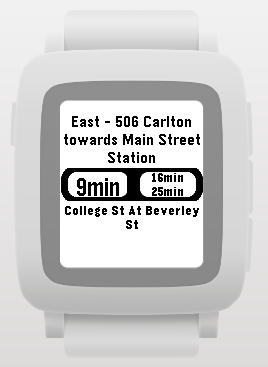

The real-time information display needed pagination because a single route can have different paths to reach its destination (e.g. “via King St.” vs “via Queen St.”), and also because there can be TTC notifications (delays, temporary diversions, etc.). Text fields had to be carefully positioned and centered to account for Pebble Round, and since I could not find an existing UI element to display (up to) three time predictions (and emphasize the first one), I manually drew it with a few ellipses.

That display updates every second, and I had to use a timer (instead of, say, a wait/sleep loop), to save battery and keep the UI responsive, and be careful to stop it during the refreshes that happen every 15 seconds. I also realized that users are unlikely to care about the app after they join a crowded bus, so this window closes itself after a few minutes without interaction, avoiding an unnecessary battery drain.

I’m by no means a C expert, but tried to modularize the app as much as possible. Since there isn’t an agreed standard on Pebble app organization (complex apps are often implemented a couple of gigantic source files), I decided to separate windows and layers in individual header/source pairs, also isolating common functionality like Bluetooth communication and string buffer manipulation.

Finally, the most important thing: I limited the C code (which runs on the puny Pebble) code to the interactive parts. Anything that could be moved to the phone or the server (where resources like CPU and memory abound) was moved. Pebble provides great mechanisms for that, as long as you keep the Bluetooth message count low: grouping the menu items instead of sending each one in its own message dropped the display time from half a minute to a fraction of a second.

Phone (JavaScript)

One of the secret sauces behind Pebble’s low cost and battery consumption (when compared to the likes of Android Wear or Apple Watch) is what it doesn’t do: instead of having a GPS, an advanced CPU or web connectivity, it piggybacks on the phone for those tasks, by means of Bluetooth (LE) communication.

You can build “companion apps” to provide that functionality, but the easiest approach is to code the phone part in JavaScript. The SDK bundles your JavaScript with the compiled binary, and the Pebble app on the phone (which is already required to use the watch) transparently runs it when the app is launched, exposing features such as web connectivity and geolocation regardless of the phone OS.

(Don’t confuse that with Pebble.js, which is a way to write apps 100% in JavaScript. It is more suited for less interactive apps, and was not used on this one.)

Parsing the responses from my JSON API (stops and routes) and TTC’s XML API (predictions) would have been cumbersome in C, but is quite easy in JavaScript. I’d have loved to use parsing APIs, but those are cumbersome to run, so I coded some minimalistic parsers (an approach I’d never use if the sources weren’t myself and a very stable API).

Again I split this part in modules that dealt with geolocation, external communication (fetching from internet APIs) and watch communication (Bluetooth), wiring them up asynchronously - a requirement to keep single-threaded JavaScript runtimes responsive.

Server (Ruby)

The server would have two tasks:

- Fetch the buses and routes once a day;

- Expose an endpoint that, given a latitude/longitude pair, returns the ordered list of stops and routes (which the Pebble just displays) and the endpoints where the predictions information can be found for each stop + route pair.

Choosing the Technology

I wanted the server to be as simple as possible (my goal here was to learn about Pebble / constrained devices development), so my first impulse was to make it quickly with a Ruby On Rails API-only app, storing the route info on a “process-less” SQLite database.

I know what you are thinking: “Ruby/SQLite are slow/won’t scale”. Well, given we have a single, read-only endpoint (the daily fetch can just rebuild the whole database) that I believed could be easily optimized to retrieve all the needed info on a single query and return the data with very few calculations and manipulations (see below), I believed this setup would be super quick under moderate load. But what would be that load? Let’s estimate:

We start by acknowledging that app usage has a hard limit: the number of Pebbles in Toronto. We don’t know this number, but we can estimate it by multiplying the number of Pebbles sold (1.5 million in early 2015, which we could project for the future - when Pebble had one, at least - say, tenfold to 15 million) by the percentage of Toronto residents over the world population (2,6 million from 2011 census / 10 billion, says UN = 0.026%).

Let’s throw in the fact that, between wealth and hispterism, Torontonians are four times as likely to use a Pebble than average population, and let’s be even bolder and assume our humble app is proportionally as popular as, say, Snapchat on Android (around 15% of active phones use it at least once a day), and we’d have 234 users per day. If all of them use the app within the rush hour (which we’ll treat as a period of just one hour, again for the worst case), we have a little less than four queries per minute.

I’d say Rails and SQLite on a tiny server can handle that.

Geographical Querying

We need to display the stops that are closest to a user’s location (and the routes inside them), ordered by distance. This isn’t a trivial problem (production systems often use GIS-enabled back-ends and databases such as Solr and PosgreSQL for that job), but we can make it tractable on our minimalist server.

Say we had all TTC stops on an ordinary map (like the one on this PDF). To find which stops are closest to a given location, we have to measure the distance between that location and each stop - a time-consuming task, regardless of you being a human with a measuring ruler, or a computer applying the Cartesian distance formula. But let’s think again: do we need to measure all stops?

Not really: a person is only interested in stops that are within walking distance - let’s say, no further than 500m from their location. A human could just use a drawing compass to draw a circle around the location (with a radius equivalent to 500m on the map’s scale) and calculate the distance for those in a much more reasonable time.

For a computer it doesn’t make things better, because finding which points are within a circle (or “circular geofence”, as GIS people call it) still requires it to calculate the distance between the circle’s center and each point. But what if we consider a square fence, instead of a circular one?

Let’s imagine a 500m x 500m square fence around the location, delimited by points (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂). If we name the user location (x, y), these values are easy to calculate (x₁ = x - 500, x₂ = x + 500 and likewise for y//y₁/y₂).

We know that all stops whose (x, y) obeys x₁ < x < x₂ and y₁ < y < y₂ are within the fence. Gathering them is much easier with that in mind, because we benefit from an index for at least one of the ranges (both if the database is smart enough).

We still need to calculate the distance between the location and each stop in order to sort them, but it will be just a handful of stops at this point. I’d rather have the database (rather than notoriously slow Ruby) doing this work, but I can’t directly ORDER BY distance because SQLite doesn’t have the square root or exponentiation operations that appear on the distance formula, that is: D(p1, p2) = √[(xₚ₁–xₚ₂)²+(yₚ₁–yₚ₂)²]. We can replace the power of 2 is just a single multiplication, but the square root is a pickle.

The good news: we don’t want to calculate the distances, we just want to compare them. And it is easy to prove that if a positive number’s square root is greater/equal/smaller than another number’s square root, the number is also greater/equal/smaller than the other. That is: comparing the square root of two numbers is the same as comparing those numbers, so we can drop the square root and ORDER BY (x-stop_x)*(x-stop_x)+(y-stop_y)*(y-stop_y).

There is just one tiny little fact (which is probably making geography-aware readers cringe at this moment) to consider: the Earth is round. Latitude and longitude are not Cartesian coordinates on a map - they are angles. And the actual formula to calculate the planified distance

That means we can’t simply treat latitude and longitude as Cartesian coordinates, because they are actually angles. A distance isn’t a straight line - it is a curve over the surface of Earth, and calculating the distance between a pair of latitude and longitude coordinates requires much more complicated formulae, because even the fact above isn’t that true (the Earth is ellipsoidal, complicating matters even further).

It turns out our app doesn’t need to care about that. Why? Well, for very small distances (in an Earth scale), the error is also very small. Its exact value depends on the latitude due to factors that include the ellipsoidal nature of Earth mentioned above, but for sub-KM distances in Toronto’s 43°42′N latitude (and the fact that we are mostly interested in the relative distances, not their absolute values), we have enough precision for our use case.

Final Results

Wiring all that together was a fun exercise over all those topics - and in the end we now have an app that lists the stops and routes with a single button press in a couple seconds. Once the route is selected, predictions pop up just as fast, allowing us to make reasonable decisions on whether to go to the bus/streetcar stop or stay warm at the nearest Tim Hortons.

Just as importantly, I played with things that aren’t usually part of my days at Shopify: embedded devices, C, non-web JavaScript and geographic math hacks. The source code can, of course, be improved (I’d sure look C and JavaScript test frameworks, because these days I feel naked without tests), but can be used as a basis for likewise apps. That, of course, assuming Pebble’s new owners continue to use its operating system - it would be a waste if they just canned it. Let’s wait and see.